Meribah: Striking the Rock

Moses saw only from a distance,

Not a single toe

Into the promise.

But he saw.

An old man atop Pisgah,

With eyes still bright and clear,

He witnessed the far-off treasures

That he would never touch

Stored up for his children.

And that was enough.

I used to think this a cruelty:

The bitter whim

Of an inscrutable God.

And perhaps it was.

But now,

With my life

More than half spent,

I see the miracles

Yet to take place

For my children.

For my Black children

And my beautiful

Black and Yavapai grandchildren.

And I am content,

Working for their promise,

And for the promise of their neighbors,

And all their children after them,

Even if I never step into that promise,

With my own pale feet.A few years ago people all over Southern Arizona started seeing something we’d never seen before. For millennia, as far as we knew, our beloved and stately saguaro cacti had always bloomed the same way and at roughly the same time.

There is perhaps no more famous cactus than the saguaro. With its enormity of height and human-like arms, the saguaro has become the thing most people see in their mind’s eye when they think of a cactus, and it was even chosen to represent the cactus emoji (🌵). Its blooms are the Arizona state flower, and its fruit are one of the rarest and most sacred foods on the planet. The entire calendar for the Tohono O’odham, the ancestral indigenous people who still live here, revolves around the harvest of the saguaro fruit, and their most sacred rituals are part of that harvest.

For thousands of years, Tohono O’odham harvesters would go out into the desert at this time of year to watch the fruit develop, singing to the doves who signaled when the fruit was finally ripe. Then, using long picking poles made of ribs from dead saguaros lashed together with a creosote branch across the top, they would harvest the precious and sweet red flesh from the crowns of the cacti and tips of the arms. (See the end of this article to read more about my seventeen years of participation in this sacred harvest.)

A few years ago, however, we saw something perhaps no one had ever seen before. After a deadly drought that killed many of the cacti and other native plants, the saguaros started sprouting flowers all down their trunks instead of just at the tips of their heads and arms. Some people called it a superbloom. Others said it was a sign of climate change. Some said it was a harbinger of trouble.

It turns out, they might have all been right. After some research, local botanists working with scientists from other parts of the country that had suffered similar droughts discovered that a similar thing had happened with certain types of conifers in the Pacific Northwest. Instead of producing their usual seasonal array of pinecones, under the stress of a prolonged drought, the pine tries started making a massive amount of cones — many times more than had never been seen before.

And then they started dying off.

Scientists learned that this was a clever, if suicidal, adaptation. The pine trees could revert cells called areoles, switching them from making new branches or needles back into cone production. Somehow sensing the drought, the trees used their energy reserves to make new seed-bearing cones instead of growing as usual, increasing the chances of survival for future generations by this mass profusion of seeds.

Scientists here studied the saguaros and found that the same thing was happening here. Due to multiple years of stress, saguaros were switching off the genes that make spines along their trunks, converting them back to being able to produce fruit and flowers. The term most scientists have adopted for this new saguaro phenomenon is “side bloom.”

Sure enough, after that year of nearly ubiquitous side bloom, saguaro deaths in the Sonoran Desert increased sevenfold in areas where saguaro deaths were tracked.

Not all of the saguaros that side-bloomed died, however. Fortunately, we got late summer and winter rains, and despite the alarming number of losses, many of the saguaros did survive. I think we collectively breathed a sigh of relief after that, hoping this was a sign that saguaros, along with our other beloved indigenous plants and animals, would adapt to a rapidly changing climate. In fact, after the superbloom, many reported seeing a vast increase in insects and lizards, which then led to an increase of other animals and birds. It seemed like the desert was finding its equilibrium after a harsh, but hopefully isolated (or at least rare) event.

Well, here we are just a few years later, and the side blooms are back after yet another historic year of drought and record heat.

Not only that, but last year we had record windstorms, including tornadoes, which have never been reported in Tucson before this. Thousands of saguaros, which only grown in this one small region of the world, were toppled in the severe storms. Some of my favorite trails are littered with the remains of hundreds of fallen cacti, and now, after this year’s horrific drought, the ones that survived are suffering.

In my Everyday Divinas practice I have meditated with a few of these side-blooming cacti, opening myself to any meaning or wisdom I can glean. At first I thought about how I so often deplete myself to utter exhaustion and even sickness in order to make life better for other people. This has been something I’ve done all my life as a codependent person, but now that I’m in my fifties, my reserves are lower and my recovery takes longer. I simply can’t continue producing beyond my capacity.

This has been a major theme in my Divinas practice lately, almost certainly due to the fact that I’ve been over-hosting and depleted for several months now. Just as the desert has had almost no rainfall, I haven’t been nourishing my own inner landscape with alone time and rest. And yet, like the saguaros here and the conifers in the Pacific Northwest, I find myself committing to more and more despite the withering.

Seeing the consequences of this in the natural world was a firm but gentle reminder that I am responsible for my own “spiritual climate,” and I am not at the whims of the weather. The saguaros and pines may not be able to make it cool off or rain, but I do have the ability to manage my own life to a great extent, and just as plants need rain, I need time to recharge in solitude. I simply can not nourish my spirit in the onslaught of a metaphoric heatwave of stress, distraction, and productivity.

And so my husband and I decided that we would take an intentional break, swearing off hosting for the entire month of June. We canceled almost all of our plans and I’ve kept my calendar light on purpose. We’ve even decided not to host a party for my birthday (June 24th), which is something I’ve done every year for as long as I can remember.

At first, this was an incredible challenge, and it produced almost as much stress as over-hosting. But my husband and I were (and are) committed to a reset and to restoration. As I write this, we are in the second week of saying no to hosting, I came to realize that I have developed a compulsion toward hospitality since Covid. This is not a bad thing in and of itself, but as is true in many codependent traits, I can take a good thing too far so that it becomes a character defect. My ability to care for, connect with, and love my friends should come from the heart as an act of intention rather than a reflexive impulse, and it certainly shouldn’t come at the expense of my own physical, mental, and spiritual health.

As I’ve had time to rest and reflect, though, I’ve noticed that the side-blooming saguaros have had another message for me.

These plants that adapt to impending doom by producing all that fruit aren’t just sacrificing themselves for nothing. There is a sort of muscular hope in the idea that even in the face of historic droughts and crushing heatwaves, these plants don’t just hibernate or horde resources. They don’t just shut down. They do their best to create future abundance that perhaps only distant generations will see.

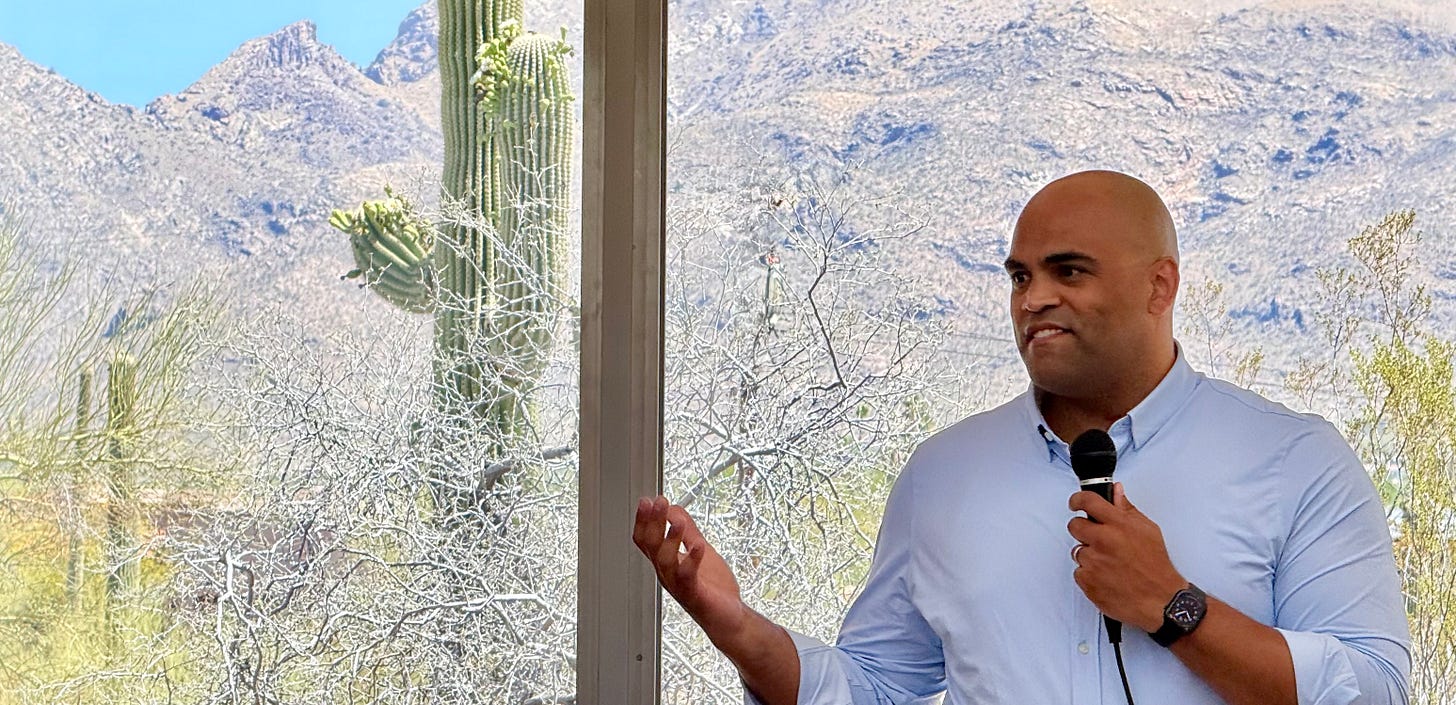

Last weekend we got to meet Colin Allred, the civil rights attorney and former congressperson. My husband and I helped finance a small event for men who support progressive women in politics, and he was the keynote speaker. He said a lot that was inspiring, which I might write about at a later date, but what really stuck out to me in the context of my recent meditations was when he said:

“I am not going to be the one who drops the baton in the relay race for democracy. I’m a huge believer in Doctor King’s idea that the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice — but it doesn’t bend on its own!”

In today’s world, it can feel like we are in a severe drought of positive news, suffering under a heatwave of political corruption, war, violence, inequity, and injustice. “Climate anxiety” has been an important field of research with mental health organizations, and every single one of my therapist friends or acquaintances has reported a massive surge in anxiety in their patients related to world events. Some are calling it “existential angst,” because it can be intensely stressful to simply exist in today’s world.

When I heard Allred talking about not losing hope and actively bending the moral arc of the universe toward justice, I noticed that there was a side-blooming saguaro outside the window right behind him. Then, at that moment, he talked about how his forefathers lived in Texas back when they weren’t even allowed to vote, and now here he was as an elected official in that same state. Maybe they didn’t live to see it, but that didn’t keep them from working toward the goal anyway. He was enjoying the fruits of his prior generation’s work.

As he had mentioned before, the outcomes we want are often the result of a relay race instead of a sprint. We aren’t individually responsible for the entire future — just the part we are supposed to carry.

One of my favorite theological philosophies is the Jewish idea of Tikkun Olam, which translates to repairing or healing the world. In reference to this, Rabbi Tarfon famously said, “It is not your duty to finish the work [of repairing the world], but neither are you at liberty to neglect it.”

I’ve been chewing on that idea a lot lately. These same side-blooming saguaros that are overproducing for future generations are not necessarily all going to die off like the conifers did in the Pacific Northwest, and not every saguaro is side-blooming either. Plus, the bodies of the saguaro are uniquely able to store water. Compared to the rest of the world, the desert is in constant drought, and the only things that live in these conditions are adapted to thrive here.

Saguaros have done so not just through self-sacrifice, but also through self-preservation. They have learned to store up to two tons of water inside their bodies, and their ridged trunks expand like an accordion during wet seasons so they can soak it up and store it for the future.

Also, as a community, some may be sacrificing themselves, but others are adapting in other ways. Scientists have recently discovered that while saguaro seedlings are unable to grow as usual with our steadily climbing extreme heat, many more are sprouting up on rocky land where water doesn’t soak into the ground as quickly. Seedlings and young saguaros are following the water sources in ways they may never have had to before — but they are still able to figure out new ways to survive.

These ideas coalesce to give me a type of dynamic hope, eager to both store up my reserves and also to be more intelligently productive. I don’t need to sacrifice myself for future generations. Martyrdom is a bedfellow to codependency, and I no longer need to bolster a fragile self esteem with acts of self-sacrifice. But that does not mean that I don’t also want to do my portion to repair the world — to carry the baton for my leg of the relay race toward a better future.

Three of my grandchildren are of Zambian and Yavapai (Native American) heritage. They were here a couple of months ago to celebrate my oldest grandchild’s birthday. Adonis is so bright, so beautiful, and so incredibly kind. As he and his sisters frolicked in the pool for his birthday party, I couldn’t help but delight in all the promise they represent. And yet, always looming, are the specters of racism, inequity, and other institutionalized hardships that they will likely face. Indigenous and Black Americans are far more likely to be abducted, murdered, face discrimination, or go missing, and here were three beautiful native/Black children and their Yavapai mom, celebrating together in giggle fits and splashing.

Both of these things exist at the same time: the celebration and the sorrow, the potential and the risk.

Neither the sorrow nor the risk outweigh the fact that I can do my part to repair the world for their sake. It is not my duty to finish the work of repairing the world, but neither am I at liberty to neglect it. In all honesty, because the world is full of other broken and hurting humans like myself, it will never be entirely fixed. The Promised Land is a beautiful idea and metaphor to work toward, but I am not sure I believe in the possibility of an actual utopia. But does that mean I’m giving up? Absolutely not.

As Colin Allred mentioned, in the same place where just a generation or two ago people like him couldn’t even vote, he now enjoys privileged status as a successful force for good. If he can have faith for a better future in Texas, I can surely work toward a better future for my children and grandchildren here, and I can do my part to heal the world elsewhere as well.

Would I die for my grandchildren? Probably. But is that what I’m being called to do right now? No. And me being a positive force in their lives is far more valuable at this point anyway. So, in looking back at the saguaro as an example, I can store up sustenance for them the same way the cacti store water to withstand extreme conditions. I do that by having college funds in their names, by working toward their legal protections, by doing my part to make the world more fair, by creating a safe space for them to be deeply loved and supported, by supporting their mom, who isn’t even with our son any longer. And I also do that by taking care of myself so that I have time for them and don’t show up in a state of resentment or depletion when I do get to see them. I do that by taking care of myself physically so that I can support them as long in this lifetime as I can. And I do that by saying no to other things.

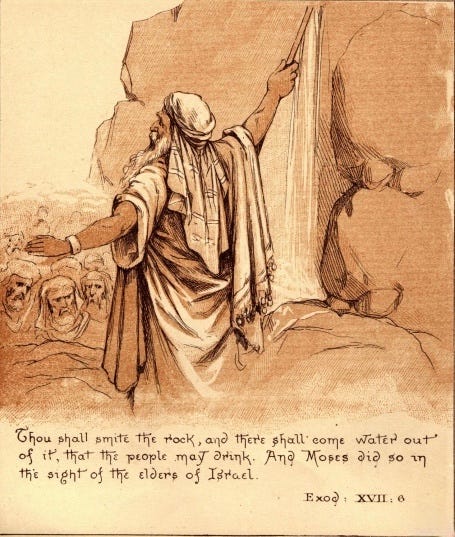

There’s a story in the Exodus tale that used to vex me. It is recounted three times (with variations) in Exodus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, and this story used to trigger extreme perfectionism in me. In the story, the Israelites are wandering in the desert and they think they are going to die from a lack of water. In one account, God tells Moses to strike a rock and water will miraculously come forth, and in another God tells him to speak to the rock to produce the miracle. Well, in both cases, he messes up, and so he is barred from ever entering the promised land.

In the case where Moses is told to tap the rock once, he hits it twice, and in the case where he is supposed to speak to the rock, he hits it instead. Some rabbinical records argue that the real sin was that instead of speaking to the rock, Moses spoke to the people. Either way, Moses didn’t follow the command exactly and to the letter, and so he was punished. Instead of seeing the fruits of his entire lifetime’s labor, he only got to see the Promised Land from a distance.

I used to shudder at that story of a capricious and vengeful god, testing his servants to see if they would err by a single word or deviation. I was reminded of this story, though, as I thought about my grandchildren, about the saguaros, about Colin Allred and all the LGBTQ people who enjoy more freedoms and security than people like us would have had in past generations. Sure, there are still places where I cannot be completely safe as a gay intersex person, and there are people actively trying to take away my rights (several groups are slated to bring cases against gay marriage to the Supreme Court in the coming months).

Still, though, the arc of the universe has bent toward acceptance and inclusion for people like me, and the bending of that arc happened over generations. Activists, protesters, politicians, and allies, from Stonewall and the Radical Faeries to Elizabeth Taylor and Tammy Faye have sown seeds that they would not see grow to completion. As a queer kid in the 90s, I never thought I’d see legalized gay marriage or intersex people like me represented in books and movies. That all came about through generations of people repairing the world, each one running their leg of the marathon in the race toward equality.

And that is what I plan to keep doing. I’ll continue the wise strategy of the saguaro, storing up extra sustenance when I can so I can bear extra fruit when I need to, finding new ways to grow and securing the future for generations I will never see grow. It takes a saguaro sixty to seventy-five years to grow its first arm, so I almost certainly won’t be around to see the seedlings from this year’s side blooms grow into adulthood. But I have faith that they will be there, growing and storing water and making seeds long after I’m gone. And at that time, maybe my own great-grandchildren will feel connected to their land and safe there, harvesting fruit from those saguaros like I do today, even in the blazing heat of Tucson summers. And that is a future worth working toward.

Meribah: Striking the Rock Moses saw only from a distance, Not a single toe Into the promise. But he saw. An old man atop Pisgah, With eyes still bright and clear, He witnessed the far-off treasures That he would never touch Stored up for his children. And that was enough. I used to think this a cruelty: The bitter whim Of an inscrutable God. And perhaps it was. But now, With my life More than half spent, I see the miracles Yet to take place For my children. For my Black children And my beautiful Black and Yavapai grandchildren. And I am content, Working for their promise, And for the promise of their neighbors, And all their children after them, Even if I never step into that promise, With my own pale feet.

I love you,

Eric

PS: if you’d like to read more about the sacred Tohono O’odham saguaro harvest and the way it changed my life, you can find my 2023 essay about it here:

Where do We Really Belong?

The Bible of Cliffs and Mesas (Courtesy The Concrete Desert Review) The long spine Of harder stone Sifts up through the sands Of millennia. Not too far away A green gash Bleeds life To everything in its fertile valley. Impossible spires Suspended in carved stone Point upward In giant gestures, Sign language Shushing us all into quiet observation I…