The Bible of Cliffs and Mesas

(Courtesy The Concrete Desert Review)

The long spine

Of harder stone

Sifts up through the sands

Of millennia.

Not too far away

A green gash

Bleeds life

To everything in its fertile valley.

Impossible spires

Suspended in carved stone

Point upward

In giant gestures,

Sign language

Shushing us all into quiet observation

In this library of sand.

Let the silence lead you

Into cricket chorus.

Let the cicada song

Lull you into peace.

Let the wind in the cactus spines

Whisper its softness

Even as it weaves

Through tiny pointed forests.

When the rain comes

You smell it first

In the cool blast

Of heavy air,

Water falling

With such weight

And value

As if life itself

Is meant to rush,

Descending quickly

To the earth.

And isn't that true?

Life rushes quickly

To where it belongs,

And we fall headlong

Into fate or purpose

Until we land

On rocks that repel

Or places that drink us up.

This is just one teaching

In the desert's books

Written in dry rivulets

And flat mesas,

And preached

In rustling cottonwood leaves.

Remember:

This place was home to others

Long before it was holy to you,

And you tread upon red rocks

That commemorate their blood

Even as we build our mansions

And drink the ancient water

From hidden wells.

But it is our home now too.

We live in two places:

The holy desert

And the killing hills;

One foot on each contradiction:

One foot intruder,

And one foot guest.I wrote that poem after one of the most significant losses of my life: when I lost part of myself that I never really had a right to claim.

I thought of it again this week when, after an intense session with my therapist, I decided to go for a hike even though it was blisteringly hot. Overwhelmed, I knew I needed to be out in nature. One of my favorite trailheads is just down the street from my therapist’s office and I had extra bottles of water in my car, so I set out alone on the trail. I needed to process, so I decided to make this week’s Divina practice out of it. As soon as started walking I was greeted with the familiar arms of thousands of saguaro cacti, outstretched as if welcoming me.

I have a deep relationship with saguaros. As I’ve written before, for seventeen years I was part of the sacred saguaro harvest, one of the most important rituals for the Tohono O’odham Nation, and something I took on with great personal importance.

It all started in June of 2001 when I had planned on volunteering for the tribal office of the EPA with my dad, who was visiting Tucson for the first time. The EPA office in Sells, the Tohono O’odham capital, had suffered a death, so they closed for their co-worker’s wake and funeral. The director said that if we really wanted to do some volunteer work, he had a friend, Stella Tucker, who was leading the saguaro harvest for the tribe, and she needed help chopping firewood.

My dad and I set out to chop wood, even though it was blisteringly hot. When we showed up to Stella’s ancestral saguaro camp, Cipri, a medicine man with a family camp down the trail, immediately took an interest in us, saying that I’itoi (the Tohono O’odham Creator) told him in a dream to expect some important visitors.

When he found out that my dad was visiting for my birthday, which is June 24th, Cipri’s eyes grew wide, and then he and the rest of the folks at the camp started having an intense conversation in O’odham. He started asking some other questions, and as we answered them their excitement seemed to grow. They then asked us to come back at sunrise the next day.

We woke up before dawn the next morning to make the hour-long drive to the saguaro camp with no idea of what was in store. When we got there, they seemed cautious but warm and welcoming. Stella took us aside to show us how to harvest the saguaro fruit and explain a bit of the customs. Then she gave us a couple of kukuipad, picking poles made of a creosote branch lashed across saguaro ribs.

My dad and I set out into the desert on our own, carefully pulling down the sacred fruit. Using the traditional method Stella had just taught us, we used the dried calyx of the flower to cut open the pods to remove the red and glistening fruit inside, putting the clean saguaro pulp into plastic five-gallon buckets — the only modern concession in an ancient and holy ritual.

We were awestruck at how much fruit there was. Some cacti only had a few scattered pods atop a lone head, but others had multiple arms, each holding dozens of sweet, sticky fruit. After a few hours, the heat became too intense and we had consumed all of our water, so we headed back to the camp with our buckets. Between the two of us, we had gathered almost exactly five gallons of crimson fruit.

What we had not known was that this was the last part of their test. We were disappointed that we’d only managed to fill a single bucket, but it turns out that this was a record harvest. None of them had ever gathered that much in a single outing, so it was remarkable that two newcomers to the harvest — much less a couple of white people who had no previous connection to the culture — would be able to gather so much in a single outing.

Cipri was ebullient with joy. Stella and Anna were both laughing and crying. It was by far one of the most affirming things I had ever experienced. We were instantly made part of their family, and they told us that yes, we were the ones they’d been waiting for. This was a dream come true.

After a few more days, they told us that they had talked to the elders and wanted to induct as as honorary members of the Tohono O’odham Nation. My new O’odham name was Juñ, the same name as the intensely sweet form that saguaro fruit takes when it dries in the sun.

The patron Saint of the saguaro harvest is John the Baptist, whose birthday I share. Also, I was a Christian minister at the time, and I was also vegan. Later, Cipri and Stella would tell me that these were the first clues that I was the one Cipri had been expecting, because of my similarities with Saint John. Our affinity for the culture, positive attitudes, kindness, humility, respect, and ability to tolerate the heat and find our way through the desert were the next factors they looked for. Then, our bountiful harvest of saguaro fruit confirmed the deal. We were invited to come every day for the rest of the harvest, and they asked if I could be part of their Dia de San Juan mass, which was held every year at sunrise on June 24th.

We ended up going every day for the rest of the harvest season.

Once my birthday came, we all gathered in the desert for the special outdoor mass. Priests and nuns from San Xavier del Bac led the service, and then afterward we enjoyed a feast of indigenous foods, including the sacred saguaro wine. After several hours of festivities, my dad and I got inducted into the tribe as honorary members. The elders laid hands on us, sprinkled us with creosote branches dipped in water, and danced in circles around us while singing ancient songs. As they encircled us, dozens of sphinx moths suddenly descended into the circle and started fluttering in sync with the dancers, like something from a fairy tale. Then we were invited to join the circle, and we danced until sunset, completing our induction with hugs, laughter, and tears. It is still, to this day, one of the most magical and meaningful memories I have, and it had profound consequences.

By the next year, I was truly part of the family. Stella called herself my “O’odham mom,” and introduced me as her son. Eventually, Stella started turning more and more of the harvest responsibilities over to me. She let me start teaching others how to do the harvest, and she taught me the intricacies of every step. She taught me the sacred songs to open the harvest, some secret rituals hidden to anyone who wasn’t O’odham, how to make the sacred saguaro wine, and more.

When the tribal government sent students out to learn, I was often the one in charge of teaching them the ancestral ways. When our O’odham friends started dying or getting too sick to harvest, and when Stella’s daughters had all moved away, she made me promise to keep the harvest going no matter what, even if there were no longer any O’odham people keeping the tradition alive.

I had never in felt like I belonged anywhere as much as I did there. I’d had a lifetime of not belonging to anything. I had always felt like I never fit in — with my family, society, religion, community, school, hometown, even my body. I had always felt like I was living in the margins of other peoples’ worlds, just outside the realm of real belonging. But here I was being taken in like I’d never been welcomed before.

It became a foundational part of my identity. I even became the first non-native person to be granted my own saguaro camp, and I also had special permission from both the tribe and the National Parks to harvest on ancestral land even unaccompanied by an O’odham person.

A few years later, Cipri died unexpectedly, and we had his memorial service at his ancestral camp. Stella leaned on my shoulder, and through tears, said, “Cipri wanted to go out on the rain. Be ready.”

There wasn’t a cloud in the hot summer afternoon sky. As we read, sang, and cried, an owl and a hawk alighted upon saguaros nearby. “Those are his messengers,” Stella whispered. They stayed there for the entire service, watching.

When the service came close to ending, I called my dad, who was back at his home in the North Carolina mountains, because Cipri had become one of his best friends. As we talked, two owls suddenly landed on my dad’s porch railing and started calling. Just like the sphinx moths coming to dance in circles with us, this felt supernatural.

Then, as soon as they loaded the casket into the hearse, lightning flashed, clouds appeared out of nowhere, and it rained so hard we got stranded. “See,” Stella exclaimed, “Cipri wanted to go out on the rain! He was a powerful medicine man.”

This experience shook my spiritual foundations. It felt like I was living in a story from the Bible, complete with signs and wonders. I’d gone out there as a progressive Christian minister thinking I was doing some sort of amends to a people who had been brutalized by my kind, but I was still doing it all in the name of Jesus. And yet here I was seeing a spirituality just as beautiful and real as my own. Why, again, was I establishing missions to reach the “unsaved?” Was there really any such thing? It seemed to me in that moment that they would have almost certainly been better off in just about every way if Christians had never come to their part of the world.

As I wrestled with that, I did more and more with the tribe, raising money, having my ministry partners donate hundreds of pounds of clothes and other goods, setting up classes full of people who would pay Stella for the experience of harvesting saguaro. I worked with schools in Sells and Topawa, and I started studying the himdag, or traditional O’odham way of life, with a medicine woman in Topawa. And eventually, the beauty of this culture overtook me until it became apparent that I could no longer be in integrity with my changing spirituality and still call myself a Christian minister.

After a long sabbatical, I dissolved the international ministry I ran, letting go of my former self. By this time I identified more with the saguaro harvest than I did with any other part of my identity.

And yet, I would later learn that even though I had pure intentions, and even though I’d been made an honorary member, I couldn’t help but bring all of my whiteness into it. I failed to recognize that this was not actually my culture, and no matter how much I identified with it, it was not my identity to take on. I could never understand what it was like to grow up O’odham, to face what they face, to have their history, to have their ancestry, to be truly O’odham. And unbeknownst to me, in all my white sense of entitlement and privilege, I had done my own version of colonization and cultural appropriation.

For several years, Stella’s health was too bad to harvest much, and one by one, all the other families stopped harvesting on the ancestral lands due to health restrictions or death. For two years, I was the only one left at the camp most days as Stella took care of things in the city. Again, she asked me to promise not to let the harvest stop until a new generation could take over.

I made calls to my friends to come harvest with me, and it felt like we were saving the harvest. Perhaps in some ways we were, but I now recognize that this is an old trope called White Saviorism, and that became my new identity.

I really felt like a savior too. I posted about it on social media, got written about in a local magazine, was interviewed for a Russian nature program, led tours for the University and groups studying anthropology, environmentalism, or desert harvesting. It became my own little empire. I thought it was my purpose and vocation.

And then one of Stella’s daughters came back.

This should have been what I’d been looking for, but instead of being happy, I took it upon myself to keep running things. When I thought she was doing a part of the process wrong, I corrected her because in my mind she’d been gone for many years and had forgotten important steps. When she made tee shirts for tribal harvesters I insisted on getting one for myself and my dad. After all, I was the one who stood by her mom when she and her sisters moved away. Stella herself had introduced me to groups as an I’adam, the title of an official harvester. I felt entitled to recognition.

I am deeply ashamed to admit this now, but Stella was dying and her daughter was coming to claim what was rightfully hers — and what I’d promised to preserve for her — yet I was desperate to stake my claim at the camp and in this tradition.

When we finally moved my dad out to Tucson after it became clear that he couldn’t care for himself any longer, he was desperate to step back into his role as a harvester as well. He and I talked to Stella and her daughter about building a permanent structure for ourselves in the place where we’d camped for all of those years, talking about “improvements” we’d make to the site. Then, in a drunken rant one night, my dad said some awful things, made a bunch of false allegations, and effectively burned every bridge we’d built over the past seventeen years. We were no longer welcome.

This was one of the biggest heartbreaks I’ve ever experienced. Part of the pain was the loss of what I thought I had rights to, and part was the fact that Stella’s dementia had progressed so suddenly that she couldn’t defend me. Even worse, I had to come to grips with the fact that her daughter was absolutely right — I had no ancestral or cultural rights to claim any of this as my own. I had forgotten that despite my intentions, despite my love, despite my reverence and respect, despite my desires, despite all the work and sacrifices I’d put into it, and despite what anyone ever said, I was always just a guest in someone else’s culture. I wasn’t entitled to any of it.

All of this came back to me when I went for that hike after therapy. Seeing the ripening fruits reminded me of the ancient songs we used to sing to the doves who showed us when it was time to start the harvest. As I went along the trail in the blistering heat, I stopped to eat some fresh palo verde seeds. The taste immediately took me back to those years of harvesting with Stella, Cipri, Anna…so many people I once considered part of my family. I thought about how I’d give anything to be able to go back and apologize before they died, to rewrite this whole story and edit out all the ignorance, arrogance, and entitlement I’d brought to it.

I sat under an immense saguaro and cried.

I then remembered the Divina practice and decided that since nobody else was around for miles, I might as well do it out loud.

“What wisdom do you have for me, Ha:san?” I asked the saguaro.

My first thought was that I need to make amends to Stella’s daughter, who I haven’t seen since that last night in 2017. (I have now written a sincere apology letter and am figuring out the best way to get it to her.) I then realized that despite all the ways my entitlement has tarnished that experience and limited my access to it, it doesn’t change the fact that these were some of the best and most meaningful years of my life. And I can do better from now on. This situation forced me to grapple with major parts of my internal shadows, and I’m a better person because of that.

Then I remembered that the saguaro cactus, probably the most important emblem of the Sonoran desert, and the center of all of this, has only been here for about eight thousand years.

Eight thousand years! That’s just a heartbeat in the expanse of history.

All of a sudden it felt like all of human and geological history expanded before me in a grand array stretching on and on into millennia. Every place on the planet has been repeatedly colonized, changed, and exploited in some way, by ever-changing epochs cycling through time. Also, once my ancestors invaded these lands, there was no going back. Can you imagine a world without potatoes, corn, beans, squash, tomatoes, vanilla, sweet potatoes, tobacco, maple, and chili peppers — all crops unknown to the rest of the world until European colonialism? There’s no putting that genie back in its bottle. Too much history has happened and there’s no way to go back — both with the world and with me. Like it or not, we are a global culture, and there are both gifts and tragedies because of it. But there are ways to move forward with grace, equity, authenticity, healing, reparations, and respect.

This is something I have got approach with care, especially since another part of my spiritual practice is tea culture. I’m licensed with the Urasenke Foundation to study and practice Chanoyu, the Japanese tea ceremony, and I’ve studied Chinese tea culture for years with Zhuping Hodge and at the National Tea Culture Institute in China. This love for Asian culture, and specifically tea culture, goes back to my grandmother, who was Hawaiian, and who studied Japanese tea ceremony with her Japanese friends there before Hawaii was even a state. And yet my grandmother was also taking on a culture not her own. She may have identified as Hawaiian, but she was not native. She had incredible privilege, including being one of the only people, along with my grandfather, to actually own property in Kailua. Although she secretly learned ancient Hawaiian healing arts, and one of her best friends was Duke Kahanamoku, she, like me, was always just a guest in that culture. And yet it was perhaps one of her most defining characteristics.

In that moment I realized that I do not have to own something or belong to it completely in order to feel a sense of belonging.

I can belong to it — even though it does not belong to me.

And that is enough. I’ve searched my whole life for a place where I truly felt at home, and I still feel that in Tucson. Also, as I learn more about my actual ancestry, I’ve learned that my long love of Norwegian culture has real roots. After some Norwegian friends said they thought I probably had strong Norse genes in 2019, I talked to my mom, who confirmed our ancestry, which she’d never mentioned before. It turns out that she even chose my name based on it, but never thought it was important to tell me. Later I did a DNA test, discovering that I am 90 percent Scandinavian (specifically Norwegian and Swedish). That led me to do my full family genealogy, which answered so many questions.

I’m headed to Norway in a few weeks and am visiting my ancestral hometown to meet some actual distant relatives in Stryn, where my great-grandparents came from. I’m learning a bit of Norwegian and have done research into dual citizenship. With the encouragement of my Norwegian friends, I’m even considering getting a bunad, or regional costume, specifically from the region that my ancestors came from.

I realize now that I was so willing to co-opt the Tohono O’odham culture because I never really fit in anywhere until they welcomed me so wholeheartedly. And that’s okay. I don’t have to fit in, because just as we live in an intractably global society now, I also live an intractably singular life. There is nobody else out there quite like me, and that’s a gift. I may feel drawn to Norway in a similar way to how I was drawn to the saguaro harvest, but even though it is authentically my heritage, that is still not all I am. No matter how important or “real” it becomes, it will always just be one part of who I am.

Nearly everyone on the planet is a product of a global world, and to be honest, tribalism is the root of so many of the world’s worst problems right now. But the answer is not to declare ourselves citizens of all of it. My best answer is to become a citizen of myself, while also being a good neighbor to everyone else.

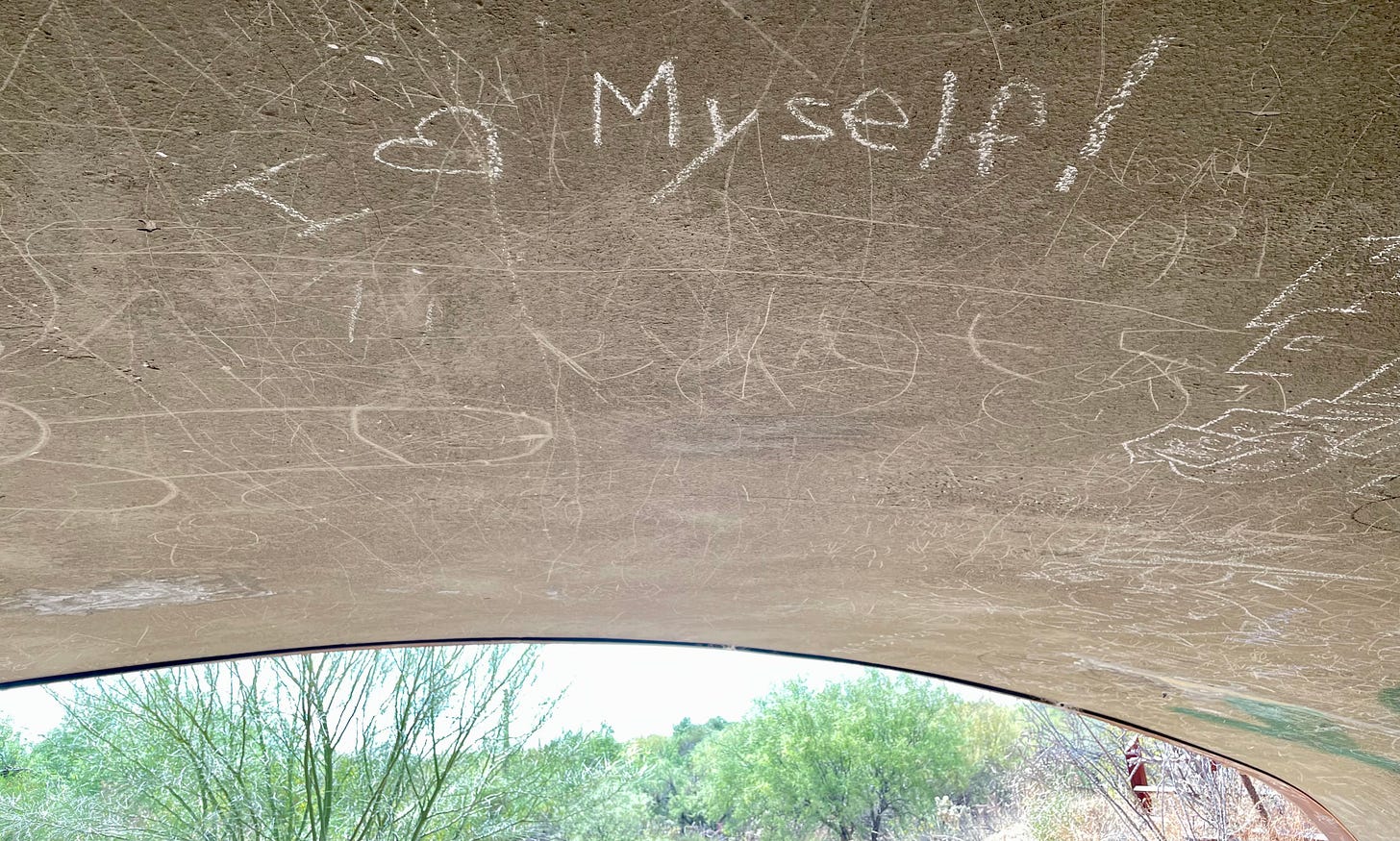

As I left the hike, feeling healed and connected to the greater world and my place in it, the trail passed under a bridge, the underside of which was covered with graffiti in chalk and paint. Along with lots of standard things like “Britney loves Mike” (and even a “Steven + Mitch”), there at the apex of the arch was the message of the day:

I love myself!

Yes, that is ultimately what I was looking for in all my attempts to belong to something. I was looking for identity, purpose, permission, moral worth, and all the other things we think we have to get from others. But my sense of belonging can’t come from others. The more I do to get to know who I really am, rather than trying to create a persona in order to fit in somewhere, the more I can feel the truest sense of belonging — belonging to this life that is my own.

It also frees me to honor all the gifts this crazy global society gives us without thinking I have to lay claim to them all. Just like we learn in tea, I can be a reverent and gracious guest.

I can just be me, and be thankful.

The Bible of Cliffs and Mesas (Courtesy The Concrete Desert Review) The long spine Of harder stone Sifts up through the sands Of millennia. Not too far away A green gash Bleeds life To everything in its fertile valley. Impossible spires Suspended in carved stone Point upward In giant gestures, Sign language Shushing us all into quiet observation In this library of sand. Let the silence lead you Into cricket chorus. Let the cicada song Lull you into peace. Let the wind in the cactus spines Whisper its softness Even as it weaves Through tiny pointed forests. When the rain comes You smell it first In the cool blast Of heavy air, Water falling With such weight And value As if life itself Is meant to rush, Descending quickly To the earth. And isn't that true? Life rushes quickly To where it belongs, And we fall headlong Into fate or purpose Until we land On rocks that repel Or places that drink us up. This is just one teaching In the desert's books Written in dry rivulets And flat mesas, And preached In rustling cottonwood leaves. Remember: This place was home to others Long before it was holy to you, And you tread upon red rocks That commemorate their blood Even as we build our mansions And drink the ancient water From hidden wells. But it is our home now too. We live in two places: The holy desert And the killing hills; One foot on each contradiction: One foot intruder, And one foot guest.

I love you,

Eric

I loved reading this, Eric. Thank you for your openness and honesty in sharing this story. To me, you have always been a citizen of yourself and a kind and true friend in writing and seeking. 🌞✨🦉

What richness we get to live! If only we could help clinging to it. So said Mary Magdalene outside a tomb one day. What is it connects us to places and cultures - is it something to lay claim to, to identify by, or is there a voice saying this too is rich, and mine to enjoy in this place and time? Love where your writing takes me wondering!