A Primer for System Collapse?

Hubris

Hubris Concepts become idols; only wonder understands. -Gregory of Nyssa What is God That we are mindful of him? And what is God That we have made him in our image? In our desire to know, To identify, To dissect and stretch and confine — Define — We draw maps Of space, Distorting the continents Of being So we can belong. Or So it can all belong To us. Our primal need to know Comes rushing, Saber-toothed, And claws Its way Into the heart, Consuming every thought. We fear what we do not understand. Will this next new thing, This unboxed Not-quite-right thing, Be our undoing? Or will it expand us Into new ways of being? New normals Are painful And are never really normal In their novelty. To change is human. But transformation is pain, And only the adaptable survive In the Passion Play of life. So if you must bring your boxes, Your catalogues, Your scholarly Latin names That you measure out upon Sacred and native tongues And bodies like mine, Which buck against definition, Know that humans only see in part. That dark glass We use to scry dim meanings Solely lets us see in shadow. More than it reflects reality, It both clouds and illuminates One’s already limited view. We can never know How much we do not know, And so I have learned to laugh At the hubris of reason, And the insatiable desire To make sense of things, At the monkey's grasp Of certainty. Like God, Like humans and apes, Like butterflies and moths, Like all that exists in this ungraspable capacity, There is more to me, And you, And all of this Than we can possibly ever sense, More than we can dare to own, More than human language Can feebly wrestle Into poems, textbooks, and Bibles. No, The scriptures evident in the vast array of stars and cells Are written with the alphabet of mystery Upon the palimpsest of time.

I grew up in a fundamentalist evangelical Christian household in the rural South, then I spent fifteen years in ministry, so you might say that, regardless of my current beliefs, evangelical Christianity will always be the “native tongue” of my spirituality, the primary culture and identity I was born into. That’s been a helpful way to look at my religious background as I’ve grown more spiritually open and mature. After leaving the faith twice now, I’ve come to realize that much of what I once adhered to remains relevant, resonant, and precious to me — sometimes even when I no longer believe it in it. My beliefs might have radically changed, but I’m still thankful for many of the ways that background and training shaped me.

When I first started seminary in the late 90’s, I vowed to read all of the Gospels and the Book of Acts three times every month. It was a lot of work, but it drastically changed my theology. I noticed minutiae I’d glossed over before, and I felt like I was getting a vibrant picture of who Jesus was and what the world he inhabited was like. It was both thrilling and painful as my old worldviews crumbled and new epiphanies came to light. In light of today’s polarized climate, the weaponization of belief, and the struggles I’ve had grappling with the world’s excessive us-versus-them systems, I’ve been thinking a lot lately about a particularly jarring discovery I stumbled across in that intense study of the Gospels: the easy-to-miss story that Jesus called both Mathew the Tax Collector and Simon the Zealot to be his disciples.

This was happening during the Roman occupation of Israel. The Zealots were a powerful political party at the time, and they would probably be called “militant Israeli nationalists” in today’s terminology. The Zealots were considered one of the major Jewish sects in Israel at the time, with similar beliefs to the Pharisees, but they were rabidly and radically anti-Rome and sought to incite Jews to rise up in a violent rebellion against their occupiers.

Tax collectors, on the other hand, were the polar opposite. They not only accepted Roman rule, but they actually worked for the Roman government, extracting taxes from the occupied Israeli citizens. There was probably no group more reviled among the Jewish population.

And yet in the story of the disciples, we see that Jesus called these two enemies together, asking them to put aside their differences in order to follow him and do good works.

This would be like recruiting an ANTIFA activist and ICE agent to set aside their differences to work toward a common cause.

Ever since I first had that realization, I’ve used that as my standard for how to get along with people who I feel are sometimes abhorrently wrong. It has enabled me to have a relationship with my mom, who is about as Christian Nationalist as one can get (some in my family describe her as being part of the “Christian Taliban” because of her extreme views). It has allowed me to remain friends with people from all walks of life and beliefs, even when they actively vote against my rights and welfare. It has emboldened me to have kind, compassionate, and respectful conversations with people who literally hate me for who I am or say that intersex people like me don’t even exist.

I’ve held this concept as a sacred standard, and it has often served me well. But lately I have been troubled by it, and I couldn’t quite put my finger on why.

Then it dawned on me: extremists of all stripes used to be pretty rare and didn’t really have a ton of power. Liberal extremists were mostly relegated to academia or the nonprofit sector and religious extremists were stuck in pockets of suburbia or political theater. Now, though, it seems the extremists have taken over. And it isn’t just here in the US. Extremism and radicalized nationalism are everywhere in ways I never thought possible.

So, in light of this, am I really called to get along with everyone? When does my peacemaking and bridge-building become enabling or capitulation? If Jesus were to walk into Congress today, would he call on AOC and Marjorie Taylor Greene to come together as his disciples, or would he be more likely to start flipping tables and driving out corruption?

I’m embarrassed to say that only recently have I realized that the Jesus of the Gospels probably wouldn’t even go into a governmental office. He never called Matthew the tax collector and Simon the Zealot to follow him by tolerating each other’s political differences. No, he asked them to follow him by leaving behind their political and national identities to start something new, something that transcended nationality or politics.

The systems of the day were failing extraordinarily. Corruption was rampant. Cruelty was everywhere. The religious powers had crystallized their doctrines into a series of loopholes that enabled the rich and burdened the poor, while the Roman Empire did the same with their oppressive laws, dividing people into free citizens and conquered subjects, the privileged and the exploited.

The social, political, ethnic, religious, and caste orders had failed, and the solution was not to choose between Israel or Rome, or even a religious sect or denomination. It was not for tax collectors and Zealots to try to be friends. It was to leave all of that behind for a new identity formed by a new community.

Contrary to popular belief, this community was not built on faith. It wasn’t about family. (See Matthew 12.) It wasn’t about belief or a moral code, but was rather about how to be a good neighbor, how to love, how to provide. And I don’t believe it was ever meant to be a government or a religion or a structure.

As Gregory of Nyssa would famously say, “Concepts become idols; only wonder understands.” As soon as we try to create a system or structure to define this community, we create borders and barriers, and we begin to idolize that structure and move away from the true purpose that holds the community together.

It sure feels like we are in a similar time. Our concepts have failed. Our governments and public institutions have failed. Our media is no longer trustworthy. Our infrastructures, our social safety nets — even our ability to trust that the Earth will continue to sustain us in an age of overpopulation and climate change — all of these are crumbling. Heck, with the rapid rise of AI, corrupt media, and legions of hostile agents spreading misinformation, we can’t even trust what we see reported as news in many places.

So what do we do when the world order is crumbling, when empires start to fall, when everything we’ve been told to work for gets swept away with the stroke of a pen in a dubious executive order, or when our neighbors are being kidnapped off the streets as we scream for justice? What do we do when our own governments murder people in the tens of thousands and then make laws to ensure the deaths of even more? (For perspective, an estimated fourteen million people are expected to die in the next five years solely due to the DOGE cuts to USAID. That’s 14,000,000 human beings who will die because of a single policy decision.)

And again, this is not unique to the government here in the US where I live. My friends all around the world are disgusted and alarmed by things happening where they live, and in today’s world, it’s more obvious than ever that decisions made in one place can drastically affect people who live in another.

So what is there to do about any of this?

My honest belief is that the only thing that will actually change this is building community that transcends boxes or labels or titles or castes or groups that divide us. Just as people in other eras couldn’t conceive of a society without pharaohs or kings or emperors or papal rule, so too do I believe we can’t conceive of what might come after capitalism, which has become entrenched in every part of our lives, from the way we treat the planet to the way we organize our cities and institutions. But capitalism will fail, just like dynasty and feudalism died out in previous societal collapses, and it will largely, if not totally, need to be replaced with something more equitable and sustainable.

As a global society, we are in system failure.

As an intersex gay man, I’ve been failed by the system more times than I can count. From being bullied in school and family, being fired for being gay, for being gay-bashed, to having no rights to marry for most of my life and for all the struggles I faced when I worked in the church, there have been very few institutions (if any) that have truly worked for me. As a person born with a rare intersex variation, I’ve been failed by the medical establishment for most of my life, and I have had to conform to a society that treats me like either a medical oddity or a freak. I had to either learn how to navigate these systems on my own and make them work for me in some fashion, or I had to create my own communities to replace them.

In fact, in 1996 I started a novel online “church” because there simply was no other place for me to find that community — so I made it myself! It was so much work, it was terrifying, and it tested every part of me, but I was desperate for community and I found other people who had been let down and rejected by the dominant systems too. So, as more people got involved, we banded together to create something new that worked for people like us, and it flourished.

Unfortunately, I didn’t know enough back then to create a community that transcended religion and Christian identity. I tried to make it open to everyone, but I was still desperate to prove that I merited belonging to the structures that existed, and so I used that platform to try to change the system instead of just transcending the system.

Ultimately, that led to burnout, because I am never, ever going to be able to fix a systemic structure that is inherently flawed.

So now instead of seeing myself called to ministry along with Zealots and tax collectors, I see myself called to leave all those labels behind, again and again, to the practice of being kind. To be loving. To be generous. To speak the truth. And maybe to flip over the tables in the corrupt spaces — and at other times to go out into the desert by myself to pray.

I’ve come to realize that all my life I had been making institutions and people my higher power. I thought I was being a “good Christian” or “following God” — and maybe I was in the best way I could at the time, but in that quest I kept trying to fit into or expand the structures that already existed.

Even when I left the church, I made other people my higher power, or I tried to be a higher power to others. Twelve Step recovery programs like AA or CoDA are considered to be “spiritual programs” because they re-examine our concept of a higher power. In these programs, we must come to believe that “a power greater than ourselves can restore us to sanity.”

We can’t stop the insanity on our own and we can’t depend on other people or systems to do it for us. We need our higher power’s help, and so we have to figure out how to trust in a higher power. I think we are in a time where it is becoming obvious that we can no longer trust in our institutions, such as government, academia, business, media, medicine, religion, or any other establishment that has been corrupted by the effects of meritocracy, capitalism, extremism, and power. We have been told all of our lives that these systems would take care of us, so when we see them crashing, we have to confront our powerlessness to do anything about it.

In some ways, we have believed in these institutions with the same unwavering faith that ancient agrarian societies placed in fertility idols and rain rituals.

When I became disillusioned with God and religion the first time, I went back to school to become a therapist and launched what would become a popular self-help business. I thought I could help people transform their lives, and I took on their burdens like some kind of therapeutic martyr.

I now realize that every time I tried to heal someone, rescue someone, change someone’s mind or heart, I was trying to be God. When I beat myself up for not knowing something, it was because I was trying to be omniscient. When I overscheduled and overcommitted myself, it was my feeble attempt at being omnipresent. When I tried to force people to change their behaviors or their beliefs, I was trying to be all-powerful. And when I had all those imaginary arguments with people, privately rehearsing what I might say or might have said differently, how was that any different than prayer? After all, what is prayer if not talking to someone who isn’t physically there?

In all of those cases, I was putting way too much trust in the untrustworthy, believing the unbelievable, and tolerating the intolerable. That’s pretty much the definition of my codependency, and it is what kept me in a marriage to a violent addict for seventeen years. At the root of all of it was the belief that I could somehow make everything right, or that I could change someone, or that I knew better, or that it was my job to sacrifice myself for others.

I’ve realized that I’ve looked at the world’s institutions through the same codependent lens. I’ve trusted that governments, agencies, politicians, non-profits, churches, world religions, corporations — that somehow the moral arc of the universe would bend toward justice, and that all of these institutions would bend along with it. But that’s not necessarily how it happens. Chattel slavery didn’t just become more humane over the years. It had to be abolished. (Well, abolished as much as it could — the Thirteenth Amendment still allows for slavery of people incarcerated in prisons and detention centers, which majorly enriches the correctional/detention industry, but that’s for another discussion…)

Sometimes systems have to collapse so something better can come along. Or perhaps more accurately, so that something else can be built in its place. We might very well be in a period of great collapse and upheaval, and none of us can predict what will happen.

Going back to Matthew the Tax Collector and Simon the Zealot, Jesus was calling them to leave behind their political and religious identities to instead focus on their humanity. Feed the poor. Heal the sick. Cleanse the lepers (which I would argue implies embracing the most marginalized of society, as the lepers were back then). Help those who have been abandoned, left behind, or downtrodden by the powers that be. And do so freely.

That is how we are going to make it through this. Instead of trusting in systems like they are some kind of invincible higher power, and with systemic failures of institutions we thought would last forever, we must learn to create our own communities of caring. I realize that this will take work, and this is not going to change the fact that people are going to die, be ripped from their families, forced into labor camps like our modern detention centers, and lose their rights. And so we need to rise up and be allies together. We need to transcend our belonging to this group or that group in order to instead trust higher power to work through us and through the connections we make.

In recovery groups, one’s “higher power” can take just about any form. In my home group, we have people from diverse faiths, sexualities, identities, income brackets, and many other defining factors. And in the group, those factors become less defining as we learn to listen to group conscience, to trust our intuitions, to place principals above personalities, to continually take personal inventory and promptly admit it when we are wrong. We ask for help. We surrender. We seek serenity. We pray:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, Courage the change the things I can, And the wisdom to know the difference.

Sometimes that’s all we can do, but the reason recovery works is because when people come in, they leave behind all the things that divide them, they work through the old labels and criticisms, they let go of control and unhealthy behaviors, and they see what they have in common with everyone else in the group no matter what their background or identity may be outside of the group.

In my group we have Wiccans, evangelical Christians, Jews, Muslims, atheists, agnostics, Democrats, Republicans, and people of several ethnic heritages. We cross social and income barriers. We have differing levels of education and vocation. We have pastors and pole dancers (yes, really). And yet, because we are all there to heal together, we respect and trust each other even with our deepest, darkest secrets. Knowing that each of us has been hurt by another person’s addiction, and that all of us are devoted to healing from that, gives us a common purpose that is strong enough to transcend our differences in order to help each other heal.

I believe we are all going to have to find or create community like that. It’s the only answer I can think of in an age as unpredictable and incessantly heartbreaking as the one we are all living in right now. And whatever it takes, we are going to have to learn to trust in something that transcends government, transcends religion, transcends race or nationalism or any other box we think we belong to.

As Thomas Merton famously said:

“Do not depend on the hope of results…In the end, it is the reality of personal relationship that saves everything.”

A group of us did just this after I left the church. In 2015 Arizona’s governor tried to institute a Muslim ban right at the peak of the Syrian refugee crisis. A bunch of friends got together to start “Arizona Welcomes Refugees” as a response to this blatantly racist and Islamophobic policy, and we started meeting at the church where I used to work. We set up a Facebook group and invited concerned citizens to meet the refugee families at the airport to welcome them with loving signs in multiple languages and a spirit of hospitality, and we set those refugees up with “adoptive” families who would help them get settled. Every month we would have an enormous potluck for everyone involved, where the refugees would get to be celebrated with food from all over the world and share their culture and language in a safe and welcoming space.

We adopted a family from Iraq and still consider them to be a part of our family ten years later.

Wisam, the adult son of that family, told me about an Arabic phrase they used: “Trust Allah, but tie up your camel.” There’s a lot of wisdom there. The age we find ourselves in is not just a “let go and let God” moment. Nor is it a time for blind faith or trying to change the world all by ourselves. This is a time to have faith in something greater than ourselves while still doing the work we need to do to go out and heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, and be good neighbors. It is in this way that we will find that a power greater than ourselves is restoring us to sanity — both individually and maybe even collectively too.

Yes, this is a time to be angry, but as Richard Rohr says;

Without spirit, rage does not transfer into compassion. Without tears, the injustice of life does not move toward caring.

We need more than rage, anger, and despondency. We need to cultivate a connection to and belief in a higher power — one not limited to religion that divides, but is rather unifying, one that transcends labels and beliefs and challenges us to transform our rage into tears of caring and actions of compassion.

This is hard. Ego, virtue signaling, the need to be right, anger, self righteousness, fear — these are barriers to real community. A few months ago I was at an event where I was sitting at a table with Jewish activists and very vocal pro-Palestine activists. An argument started to erupt when the Jewish couple mentioned the hostages and the pro-Palestinian activist angrily mentioned that “a hundred or so hostages doesn’t justify the genocide happening to Palestinians.”

As the only person at the table who knew everyone there, I mentioned that nobody in the group supported Hamas or Netanyahu, and that nobody supported the October 7th attacks, hostage-taking, torture, genocide, or any other violence. Everyone there supported the right for both Israel and Palestine to exist, and with this fairly simple intervention, the conversation turned to blaming the systems at play rather than the individuals at the table. Eventually, everyone agreed that they actually both believed the same thing for the most part, even if they held extremely opposing views. They also both wanted an end to the war and agreed that they didn’t want to be judged by the actions of the political powers at play (Hamas and Netanyahu) any more than they’d want to be blamed for Trump’s actions.

It’s hard to do this in a world where it feels like the only choices we have are to become activists or be complicit — but that’s a false dichotomy! A Jewish friend of mine recently posted that she gets called a “self-hating Jew” when she decries the treatment of the Palestinians and gets accused of being a “Zionist occupier” when she talks about her Jewishness and how important Israel is to her. Where can someone like her fit in? Why does she have to choose a side of a political issue? She was feeling so frustrated because there was just no way for her to win, and she felt rejected on both sides of the argument.

Well, one of the ways she handled this was by organizing a public event with one of her close Lebanese friends, where they called for peace and set their intentions together in solidarity. The current climate demands we ascribe to either being on one side of an issue or another, but community calls for us to transcend that and be on the side of humanity. And that’s what my friend did. She wasn’t welcome in a lot of places, so she started community where everybody was focused on love, peace, respect, and human rights for everyone.

The good news is that there are millions of us out there ready to be that good neighbor, who want to be good citizens of the world more than citizens of a country or adherents to a religion or members of an institution, and I believe we will find each other in due time. I have faith that this will happen more and more as we stop clinging to identities, and we learn instead to cling to hope, cling to purpose, cling to wisdom, and cling to each other in holy compassion and care.

Above all, perhaps this will happen when we stop blaming each other for the systems at play and instead start seeing each other as neighbors.

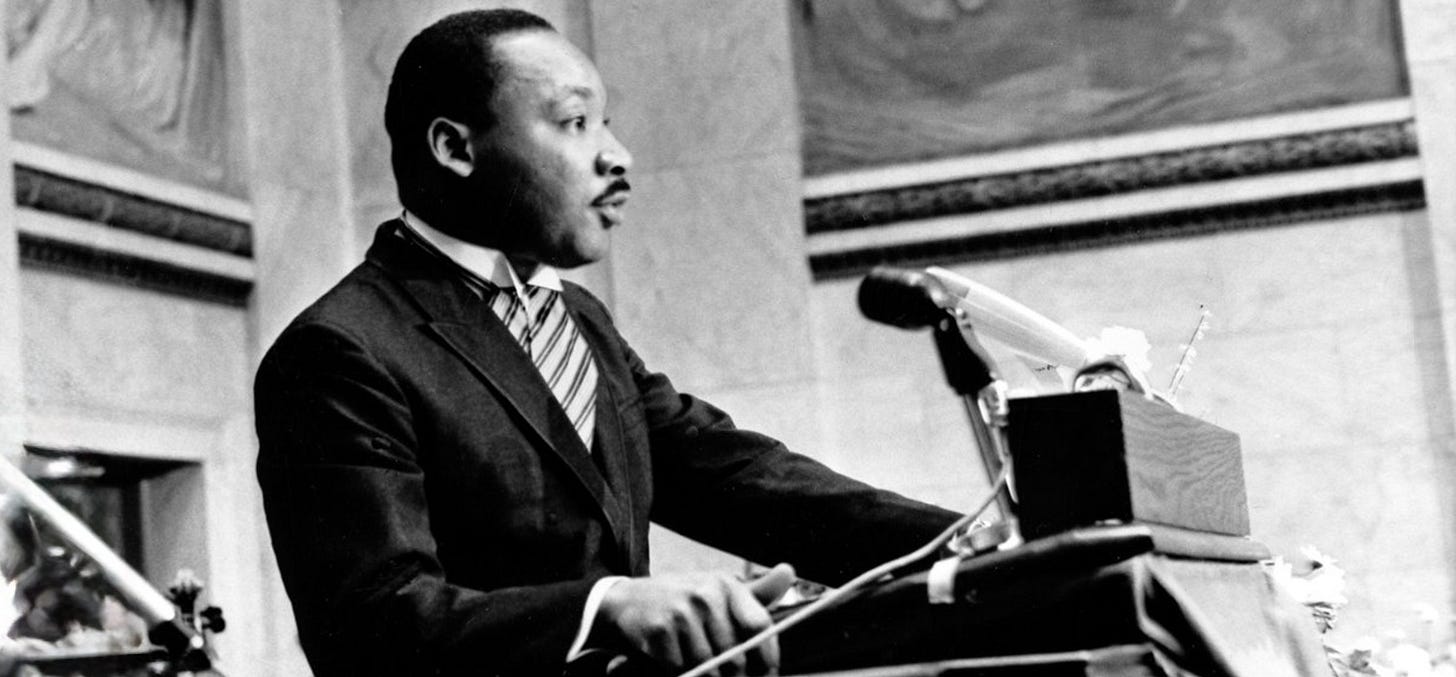

In his acceptance speech at for the Nobel Peace Prize, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr presented an analogy I think we need more than ever. He said,

“This is the great new problem of mankind. We have inherited a large house, a great 'world house' in which we have to live together– black and white, Easterner and Westerner, Gentile and Jew, Catholic and Protestant, Muslim and Hindu– a family unduly separated in ideas, culture and interest, who, because we can never again live apart, must learn somehow to live with each other in peace.”

We have to learn to live together, and to do that we are going to have to find a power greater than ourselves that can restore us to sanity. Friend, that higher power is not going to be yet another world system. It won’t be a government program, a guru, a politician, a non-profit agency or NGO, and it won’t even be the Constitution.

I’d argue that it is going to take love. I recently heard a minister who was speaking to an interfaith community say, “If the words ‘Jesus’ or ‘God’ don’t work for you, then when I say ‘Jesus’ you say ‘Love,’ and I think you’ll get to the same answers when you ask, ‘What would love do?’”

I like that. What would love do? Yes, sometimes love gets angry and demands change — but not for itself, not for ego, not for power, not for vengeance, and not even necessarily for the law. Love cares about each and every person, realizing that people do the best they can with what they have, and so it compels us to work toward a world where everyone’s has the best and most equitable opportunities. And love is a powerful force that really can change the world.

We absolutely have to learn how to share this “house” together as MLK said, and love is the way we are going to do that. We don’t have to agree with everyone in order to commit to love. And we can love our neighbors without having to take on every part of their suffering. It is impossible to end war and famine and hatred on our own. If it was possible it would have happened by now. But with love, we can help bend the moral arc of the universe toward justice, we can turn rage into compassion, we can transform injustice into caring, and we can turn enemies into neighbors.

Yes, we have to do the work, but we can’t do the work on our own, and the work will never create the world we want if it isn’t centered in compassion, understanding, and care.

I love you,

Eric

Eric, how is it that in this moment, when I am distraught and disheartened about all the things you mentioned and more, that I look at my phone and find your poetry and prose offering the way forward? Thank you. I am so glad you are here. 🏮

Oh I have so learnt from reading this and am too wanting to find allies and community… such deeply expressed wisdom.. thanks for putting this into the world