The Intrinsically Human Need for Sanctuary

Crystal River Archaeological State Park, Hurricane Helene

Note: I wrote this piece over a week ago but wanted to publish it once I had more information about my family’s condition on the Gulf Coast of Florida. My mom and I had been working on a GoFundMe for my aunt, who lost everything in Hurricane Helene and I had been hoping to share it along with this Substack entry. Before we finished the GoFundMe, however, we learned that an even worse hurricane was headed their way. Now, as I publish this, it is already starting. Rather than update the piece with new information, which will take several more days, I’ll let this writing be a time capsule, reflecting what I thought wouldn’t happen again for at least another year.

As I revisit this essay in the face of inconceivable devastation and suffering all over the world I’m struggling with old patterns of guilt from comparing my life with the lives of those who have lost so much. At the same time, I acknowledge a long history of codependent rescuing and unhealthy self-sacrifice. Whatever my work may be in all of this, I am now even more convinced of the deep, intrinsic, and universal human need for safety, belonging, security, privacy, and connection.

Thank you for reading. Stay safe.

Eric

Crystal River Archaeological State Park, Hurricane Helene “The six-mound complex is one of the longest continuously occupied sites in Florida. For 1,600 years, the area served as an imposing ceremonial center for Native Americans. People traveled to the complex from great distances to conduct trade and bury their dead. It is estimated that as many as 7,500 Native Americans may have visited the complex every year.” -Florida State Parks I grew up walking roads paved With steamshoveled burial mounds — Literal sacred ground — Shattered and strewn Onto our neighborhood streets. Native bodies From an unnamed tribe Lay curled like stone fetuses Displayed behind glass For all the tourists Who came to climb What was left of their civilization. Waves of disease had wiped them out Before settlers even arrived, And so Europeans saw this land As free And exploitable, A gift bequeathed to them By God without bloodshed. But of course there was blood: Blood in the diseases That traveled the seas, Blood in the lesion, Blood in the lung, Blood in the lacrimation Of the dying. No state park guide Or field trip teacher Could tell me how we knew their culture, Or some of their foreign-sounding words Still naming nearby places Like Homosassa, Apalachicola, And Wakulla, Or the way they lived. None could tell me How the ones buried there Had built these massive hills And monoliths So precisely to align With the heavens. But they knew my hometown Of Crystal River Had probably been lived within For longer than almost any other Florida site, A civilization many times older Than our own country, And that they traded with other nations As far away as what we call Ohio today. And, of course, that they became extinct In a tidal surge of ships. Now my aunt, Who lives beside great oyster beds Once tended by this long-dead tribe, Has lost her house Again. The second time in a year And the fifth in the last decade, As storms with European names Come with their surges of water Eroding her life And possessions Flood by bitter flood. Her once-valued property, A waterfront promise Of future value When she bought it some forty years ago, Has been laid bare like the native bodies Someone finally had the sense To reinter Back into the ground they had consecrated, Reclaimed by nature. And soon, Her life there Will be nothing but a memory too, Her long history upon her land Swept to sea Just as great steam shovels Gathered entire sacred mounds To crush into roads Before archaeologists stepped in To save what was left. There are no noble academics Or government programs Rushing to save my aunt. No, She is the disposable poor And old, Living off government checks, Having put all her livelihood Into the basket of her home. A curiosity. A cautionary tale For all those who listened To the bankers who said Waterfront property Is the surest investment of all. Tonight she cries herself to sleep, A ghost In her inland sister’s guest bed, Curled like the bones once on display In the state park’s diorama of death. How many of those huddled bodies Buried so long ago Had once been artists like my aunt, Prone to marvel and awe? And quick to dance, To celebrate, To suck oysters with ferocious pleasure, To love, And lust, Full of secret recipes, Family stories shared around a fire, With throaty laughs? Did they enjoy the humble opulence My aunt once had, Rich with the history Of her neighbors and their land, And the secret knowledge Of where to glean sustaining wealth From the plentiful rivers and bays? How many times Has my kin looked out To see the grand boulevard of light Glittering in the moon Reflecting on the wide mouth Of the river, Seeing the same scene Scattered across the palms and diamond ripples Two thousand years ago? And could those ancient people Have ever seen in all their stories And scrying of the sky The day that the ones who brought their death Would later harm the earth So deeply As to bring another deadly scourge Again to these once-holy shores? And just as archeologists marvel At their mysterious mounds and middens Denuded by disease and time, Might some future visitor Discover the old bones Of my aunt’s life Buried beneath an ascendant sea?

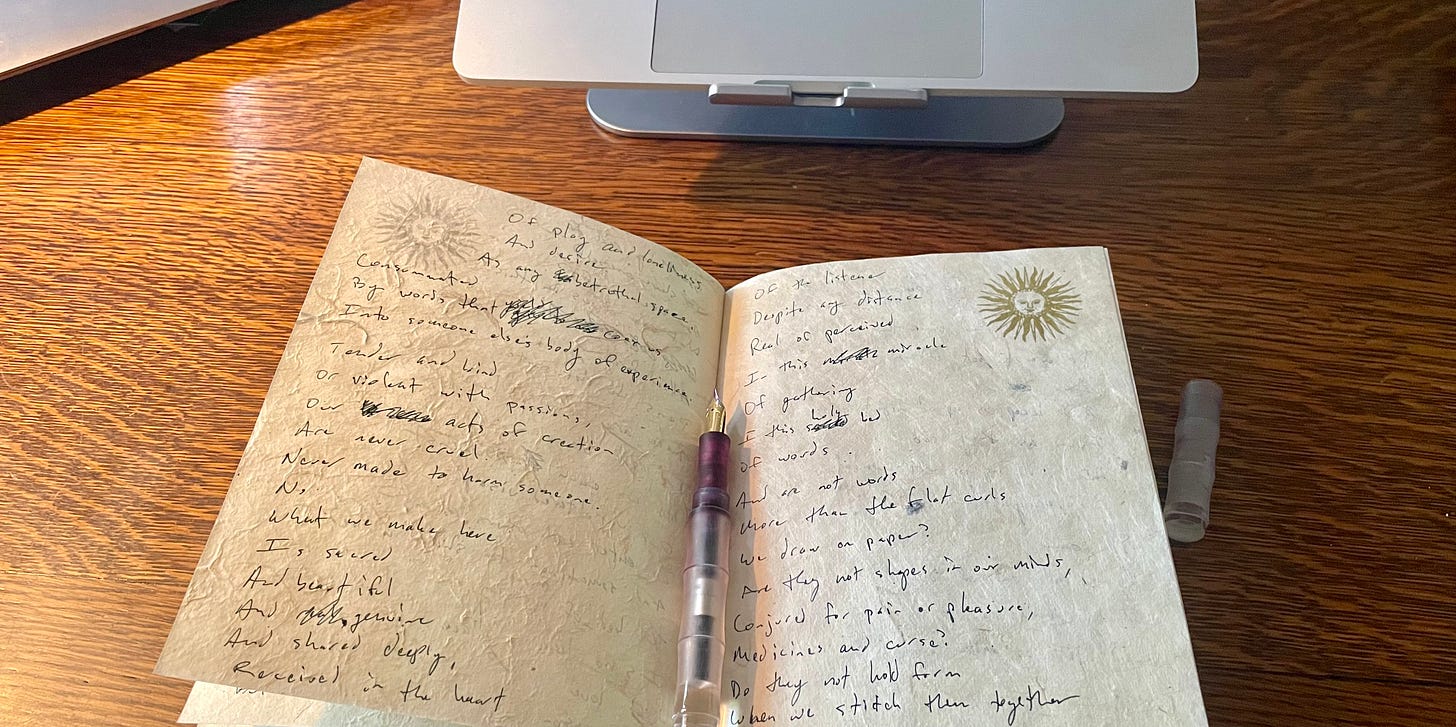

Last week my writing group met again after a summer hiatus. I’ve been a member of this group in some iteration for nearly twenty years — and yet I’ve never actually met anyone in the group. It started out on the phone and eventually moved to remotely hosted “Web meetings,” and now we meet via Zoom. Some of the members of the group have changed, as has the size and regularity of our gathering, but they’ve all been organized by Dr. Sophie Nicholls, who has become a friend, muse, and mentor over the years. (And we are going to meet in person for the first time in just a few weeks!)

Coming back together after a few months of little contact and no group sharing, I was overwhelmed by how much I realized this group meant to me. Despite never having met them, and not even knowing some of their last names or even what country some of them live in, I realized that these other writers were not just peers, but we had become a genuine community.

Sophie, having extensive experience in working with trauma survivors, is acutely aware of what it takes to provide a safe space. For those of us who have been meeting every month or so for several years, that sense of safety allowed us to sink into a nest of security, vulnerability, honesty, and encouragement. It really is a sacred space, and I realized that I needed it. It wasn’t a hobby, a mastermind group, a support group, or even a writers circle. It was my holy ground, my red tent, my virtual sanctuary.

That concept of sacred spaces has consumed my thoughts ever since. How many of us in the modern world have a touchstone like this? And how many forms might a sacred sanctuary take? Does the type of sanctuary depend on personality traits like introversion and extroversion? Are private chapels and retreats the introvert’s source of restoration, and do extroverts need big cathedrals and parks full of others who share in the experience?

Solitary spirituality has been an important part of my life for as long as I can remember. As a child I would seek solitary solace in the woods, feeling the presence of a higher power in the abundant life so viscerally obvious in the woods. That practice eventually evolved into private prayer and Scripture readings, which I did daily the entire time I was in ministry. Then, when I was exploring my spirituality after leaving Christianity the first time, I meditated alone daily, and it was just as essential as the prayer had been, or the time in the woods before that. In fact, sometimes it felt like it was as essential as breathing.

Later, though, I discovered group meditation, and I realized that there was something that changed in the shared energy of people gathering to meditate. It was similar to the feeling I got in revivals, services at the Taizé monastery in France, or prayer meetings back in my ministry days. There was a quickening and collective energy in group experience that led to deeper or heightened meditation, just like worship groups used to energize my faith.

That lasted again until I eventually found my way back to, and then out of ministry once more. The second time I left ministry was deeply painful and brought up old feelings of betrayal, abandonment, and neglect. The last thing I wanted to do was entrust a group with my spirit again.

And so I returned to the most private space of all: my shower. Each day I would let the water pour down as I prayed in the only place I felt truly alone and safe.

Since then, I’ve done a tremendous amount of healing, and now I have sacred spaces scattered throughout my life. There is my favorite spot in Molino Canyon. My back patio is another sacred space, surrounded by a rose garden I planted in my former mother-in-law’s memory. I have a secret room up in my home’s bell tower, accessible only via a trap door. It is impossible for me to not have some kind of healing experience in such exquisite places.

To be honest, my entire house is a sacred space to me. It literally used to be a church, and my husband and I brought it back from the brink of ruin in a massive renovation several years ago. I was involved in every single part of the design and picked out everything from the floor plan to the pitch of the arches throughout the property. I even put in period-appropriate doorstops and pored over online catalogs of salvaged church fixtures like light fixtures and drawer pulls.

I even designed stained glass throughout the house to designate the space, making my home a structural thesis about my life philosophy, which I call Ars Zoetica, which roughly translates to the art of the sacred life, or the sacrament of everyday living.

And yet even living in a church created to be my own personal sanctuary, I am easily distracted and overwhelmed as the pressures of everyday life, work, and relationships. They all vie for my time and attention — not to mention the constant FOMO engineered by all of our apps, devices, and social media.

The reality of this hit home several times this week as I learned about Hurricane Helene and its projected arrival in my old hometown, where most of my family still live. Sure enough, it would devastate Crystal River, along with almost the entire west coast of Florida.

As soon as the storm had passed, my mom called to let me know that she was okay, but that my aunt, Bonnie, had likely lost everything — again. Both of them are uninsured, so any loss is felt more deeply than the average homeowner. There is a new statute in Florida that allows insurance companies to cancel policies with no real notice if the home is within five miles of the coast. That includes nearly every major city in Florida except Orlando, and the vast vast majority of Florida’s population. And it includes almost my whole family who lives there, along with the entirety of my home town. Every piece of property I knew as a child can find itself suddenly uninsured — along with being uninsurable, and therefore almost impossible to sell.

Sure enough, my aunt’s home was a total loss. She had been trying to sell her home for some time, but it is a historic home directly on the water, and not up to code, and so nobody wanted to buy it, because there is simply no way to insure it. And without insurance, you can’t get a loan. Plus, although it had no prior flood history, in the past several years it has been flooded numerous times, and it is no longer habitable the way it is. What is left of the house will need to be torn down, and a hurricane-proof home will need to rise in its place — if that is even possible in Ozello, a tiny cluster of keys off the Florida coast facing ever more frequent and intense storms, coupled with rising seas.

Her property has been her sanctuary for decades. It is an idyllic spot, just feet from the water and surrounded by lush trees. As an artist, my aunt has made the home into a work of art itself, with handmade and meaningful details everywhere both inside and out. It was her own private paradise — and it was her single plan for retirement.

Back when she bought the house, waterfront property was sold as a guaranteed investment, sure to increase in value over the years. After losing much of her retirement due to a years-long string of her tax accountant’s errors, she took what she had left and put it into her property.

After the first storm, she was covered, and so she used the insurance money to rebuild. By then the property had become much more than an investment. It was like an extension of her personality, and it was a place that provided richness to her life. Also, everyone thought that storm was a freak event, and one that they would never see again in their lifetimes. Then it happened again. And again. And again. Somewhere along the way, local building codes changed, forcing people to raise their house on stilts, which was impossible for my aunt’s home. And there’s no way she could have afforded it anyway. She lives on a meager fixed income.

And so, she found herself uninsured, having to clean up and make repairs on her own with only the help of friends and family. Every year it was promised that this year’s storm was some kind of freak storm, and wasn’t likely to happen again. And now it has happened two years in a row, both times with no insurance or government help.

And Helene was the worst of all. Her house literally came apart as additions that had been made over the years split from the rest of the house in the thirteen-foot (four meter) storm surge.

She has nothing left. My aunt is literally homeless. And she has no money with which to rebuild her life.

Meanwhile, Helene moved across the Southeast with incredible ferocity. Many of my friends and family were without power, and they also found themselves suddenly uninsured because of similar legal loopholes that insurance companies exploited in Florida. Many more were uninsured because the damage caused by the hurricane is considered flood damage, which requires a specific type of coverage not included in homeowners policies. Why would someone in a mountain town worry about floods? They never had before, so there was no reason to think a mudslide would wash their house away.

And yet that is exactly what happened.

It has become evident that our old model of insurance no longer works. What was a safeguard for homeowners and a good business model for insurers in the twentieth century no longer works in this age of superstorms and wildfires.

And yet for many, home is the very definition of a sacred space, and the only place they feel safe in an increasingly disconnected and uncertain world. Most of the industrialized world has seen the erosion of neighborhoods, and now families get scattered over great distances as technology allows us to relocate, travel, and communicate over ever-expanding distances.

When I grew up, almost everyone in my family lived within a few miles of each other. Now we are spread across the country, and some have even lived abroad. I think that’s true for most people. I know very few who still live in the community they grew up in.

As much as I hated the backward culture of my little hometown, there were places there that were precious to me, and most of them are gone. The dense forest that gave me solace as a child with its giant oaks and placid ponds has been turned into a major road and a shopping mall. The coastline has been ravaged by development as much as it has by storms. And my aunt’s beautiful home is destroyed.

What do people do when they have no safe place?

I have been seeing answers to this question everywhere. The feeling of sanctuary is an innate need, expressed in childhood in treehouses and sheets thrown over sofa cushions to make pillow forts. I’ve seen how people have created that same sense of sanctuary in their homes, like I have, or in communities like churches and synagogues or other meeting places, in tight friend groups, in solitary hiking trails or picnic spots, or even public parks. I listened to a podcast where a woman who lives in New York City spoke about how her daily walk was her sacred space, because it allows her to get outside and connect with herself, providing a daily spiritual reset even though she lives in one of the most bustling cities on earth.

My online writing group with people I’ve never met has become that sacred space for me. It reminds me of the early days of the Internet, when I was just coming out as queer, and how important AOL chat rooms were for finding other people like me. I imagine this is why gay bars once used to be so important to people who felt like it was the only place they could be themselves without fear of danger or harassment.

In one of my walks this week I passed by a neighborhood park I routinely walk through on my walks. With the idea of safe and sacred spaces going through my mind, I thought I’d take a deep dive into the park and see what wisdom or inspiration it could share with me in light of these recent ruminations.

I noticed an object that looked like a memorial of some sort so I walked over to it, and I was shocked to discover a memorial to someone in my neighborhood who had been killed by a neo-Nazi for being gay.

Just moments before that I’d smiled as I walked by yard after yard with signs supporting Kamala Harris, and other signs declaring that all are welcome, that love is love, and that Black Lives Matter. Something about that made me feel safe.

And then here in that same neighborhood was the memorial for Philip Walsted, a young gay man murdered nearby in 2002 for being like me.

I wept. Yes, we’ve made a lot of progress since then, but white supremacy, Christian nationalism, islamic extremism, and other forces still pose a threat to the LGBTQ+ community throughout the world. Even now members of the US Supreme Court have openly stated that they want to overturn the decision that allowed for same-sex marriage, which would undo many of the protections my husband and I enjoy.

If that happens, would we have to move? Would we have to leave all of this behind?

I think I’m coming to realize that this need for sanctuary has and always will be ubiquitous to humanity, and that for all time there have been cultures that create sacred spaces. And for just as long there have been threats to that sacredness and safety, and yet somehow people still make it.

I remembered Esther Perel describing her childhood growing up in a community of Holocaust survivors, and how some developed crippling PTSD while others, like her parents, had somehow managed to truly come alive again after the horrors they’d experienced. She called this Post-Traumatic Growth, through which they were able to create a sense of sanctuary in their family. This had an indelible impact on Esther, and she is now one of the world’s most famous relationship experts. Would that have ever happened if her parents never found a way to find or create a sanctuary for their family as a way to heal from the horrors of the Holocaust?

With so many people disconnected from these types of places, I feel a renewed vigor in recognizing the importance of virtual and ephemeral sacred spaces. My online writing group is such a sanctuary, but could someone find the same experience with a friend or local group? Could a tiny altar built in one’s home become a place of respite and prayer? Can someone retreat into their imaginations to find serenity and safety if they cannot find it anywhere else? If even a walk through crowded New York City streets can become a centering way to create a liminal place among the bustle and noise, perhaps anything can become that. It’s just up to us to find it.

One way or another, though, I believe it is essential. Whatever your liminal place may be, I hope you find it either in an actual space or in some virtual or internal way. We all deserve to feel safe, even in the face of loss, even in the face of war, even in the face of increasingly dangerous storms and in a changing world.

This is why, just as I am committed to helping my aunt as much as I can, including working with her to set a GoFundMe (which I’ll include later), I also want to support other safe communities and spaces. I’m on the board of Yume Japanese Gardens, which is a healing place for many. I support our local art house theater, which is another community place. But where else should I be focusing my attention to fill the gaps where churches and access to nature used to be? And what about creating places where the stigmatized or the typically unwelcomed can find solace and acceptance?

I want to be part of that.

There is always, always, always some hope, some beauty somewhere, some sacred untouchable place, even if it only lives inside of us. I have to believe that if Viktor Frankl can find peace, beauty, and meaning in the midst of a concentration camp, if Immaculée Ilibagiza can survive the terror of the Rwandan genocide only to forgive the people who hunted her after slaughtering her entire family, if my friend Mike could carve out a beautiful life and find sobriety in prison, then the sacred is right there among us and within us if we only seek it out. That is the art of the sacramental life, of finding the sacred in the everyday beauty around us, of finding — or creating — the place where we truly belong.

Equally, I think my part is to help create that in the world for others whose security has been stripped away. I can’t make the world safe, but perhaps I can provide some sort of refuge for others where I can. I have to try. And in so doing, perhaps the sacred expands. Heck, maybe that’s the promise of peace on earth. Whatever the case may be, it sure feels like a worthy pursuit and a holy act.

I love you,

Eric

Crystal River Archaeological State Park, Hurricane Helene “The six-mound complex is one of the longest continuously occupied sites in Florida. For 1,600 years, the area served as an imposing ceremonial center for Native Americans. People traveled to the complex from great distances to conduct trade and bury their dead. It is estimated that as many as 7,500 Native Americans may have visited the complex every year.” -Florida State Parks I grew up walking roads paved With steamshoveled burial mounds — Literal sacred ground — Shattered and strewn Onto our neighborhood streets. Native bodies From an unnamed tribe Lay curled like stone fetuses Displayed behind glass For all the tourists Who came to climb What was left of their civilization. Waves of disease had wiped them out Before settlers even arrived, And so Europeans saw this land As free And exploitable, A gift bequeathed to them By God without bloodshed. But of course there was blood: Blood in the diseases That traveled the seas, Blood in the lesion, Blood in the lung, Blood in the lacrimation Of the dying. No state park guide Or field trip teacher Could tell me how we knew their culture, Or some of their foreign-sounding words Still naming nearby places Like Homosassa, Apalachicola, And Wakulla, Or the way they lived. None could tell me How the ones buried there Had built these massive hills And monoliths So precisely to align With the heavens. But they knew my hometown Of Crystal River Had probably been lived within For longer than almost any other Florida site, A civilization many times older Than our own country, And that they traded with other nations As far away as what we call Ohio today. And, of course, that they became extinct In a tidal surge of ships. Now my aunt, Who lives beside great oyster beds Once a tended by this long-dead tribe, Has lost her house Again. The second time in a year And the fifth time in the last decade, As storms with European names Come with their surges of water Eroding her life And possessions Flood by bitter flood. Her once-valued property, A waterfront promise Of future value When she bought it some forty years ago, Has been laid bare like the native bodies Someone finally had the sense To reinter Back into the ground they had consecrated, Reclaimed by nature. And soon, Her life there Will be nothing but a memory too, Her long history upon her land Swept to sea Just as great steam shovels Gathered entire sacred mounds To crush into roads Before archaeologists stepped in To save what was left. There are no noble academics Or government programs Rushing to save my aunt. No, She is the disposable poor And old, Living off government checks, Having put all her livelihood Into the basket of her home. A curiosity. A cautionary tale For all those who listened To the bankers who said Waterfront property Is the surest investment of all. Tonight she cries herself to sleep, A ghost In her inland sister’s guest bed, Curled like the bones once on display In the state park’s diorama of death. How many of those huddled bodies Buried so long ago Had once been artists like my aunt, Prone to marvel and awe? And quick to dance, To celebrate, To suck oysters with ferocious pleasure, To love, And lust, Full of secret recipes, Family stories shared around a fire, With throaty laughs? Did they enjoy the humble opulence My aunt once had, Rich with the history Of her neighbors and their land, And the secret knowledge Of where to glean sustaining wealth From the plentiful rivers and bays? How many times Has my kin looked out To see the grand boulevard of light Glittering in the moon Reflecting on the wide mouth Of the river, Seeing the same scene Scattered across the palms and diamond ripples Two thousand years ago? And could those ancient people Have ever seen in all their stories And scrying of the sky The day that the ones who brought their death Would later harm the earth So deeply As to bring another deadly scourge Again to these once-holy shores? And just as archeologists marvel At their mysterious mounds and middens Denuded by disease and time, Might some future visitor Discover the old bones Of my aunt’s life Buried beneath an ascendant sea?

We had a water leak in our house last winter due to an extremely deep freeze that used to be unknown in Seattle but becoming more regular. Our insurance broker warned us not to claim on our insurance because it might mean we would be refused insurance in the following year. Apparently insurance companies are doing this because they're having to pay out so often for water damage. So basically, our insurance is a waste of time.

I'm feeling quite "safe" here on the West coast but of course we have the threat of the "big" earthquake that is years overdue, so safety is an illusion. We don't have earthquake insurance, I'm not sure it's even possible to get it in an earthquake zone. I cannot imagine losing everything as your aunt has done. Our life savings are in this home, yet I recognize that really it's just a wooden construction on a patch of land that could be taken away at any moment. It makes home ownership seem ridiculous and I understand why tribes lived a nomadic existence.

Last year I invited three other artists to be part of a tiny online collective. We meet on Zoom every two weeks and talk about being an artist, the ups and downs of creative practice, how we sustain ourselves, how we want to see the world change. The group has become a lifeline for all of us. I wasn't sure if an online collective would work, but it's so nourishing and healthy and open and accepting - it is a sanctuary. We all live in different parts of the world and I think that's partly why the group works so well, we have different experiences and perspectives to contribute. It's so precious.

Thank you for your writing Eric. You have a way of connecting to the essence of what it means to be human that touches me deeply. All my love.

Sending huge love for your aunt, Eric. And to you too, of course, with a thank you for all that you bring to our group. 💜✨